“When Life Gives You Tangerines” Reflects On What It Means to Be A Woman in South Korea

☆☆☆☆ (out of ☆☆☆☆)

Oh Ae-sun / Yang Geum-myeung (played by Lee Ji-eun, better known professionally as IU; Moon So-ri portrays Ae-sun in middle age)

Yang Gwan-sik (played by Park Bo-gum; Park Hae-joon portrays Gwan-sik in middle age)

↑Note: Korean names denote the surname followed by the given name.

One of the elements that I appreciated about “When Life Gives You Tangerines” is that it took into account what life was like for Korean women — especially poor women — in the decades before South Korea became a wealthy country.

This beautifully-executed slice-of-life K-drama spans the decades-long relationship between Ae-sun — who wanted to escape Jeju-do and become a poet in Seoul — and Gwan-sik, who wanted nothing more than for Ae-sun to love him back. We watch as their relationship unfolds from their childhood in the 1960s to the present day.

Their ongoing love story is one of persistence, with a deconstructed storyline that eloquently skips around between eras. The thesis of the drama is both simple and complex: Gwan-sik is a handsome, hardworking young man whose only wish is to be with Ae-sun. Scriptwriter Lim Sang-choon deftly avoids cliches, as he delves into what makes a family, what constitutes true love, and the fortitude that women need to survive in a culture where they are seen overall as a dispensable plus-one, rather than the protagonist.

Like “Reply 1988” (which also starred Park) and “Our Blues,” “When Life Gives You Tangerines” takes you on a slow-burning journey where the action isn’t in the form of grandiose overtures, but rather the small moments that make up everyday life.

Wait, there actually is a grandiose overture that sets the tone for how much Gwan-sik loves Ae-sun. As he is leaves on a ship to go train in sports — the only thing he excels at in school — she realizes that she does love him as much as he loves her. As she calls out his name, sobbing, he hears and sees her. And without hesitation, he literally jumps overboard to be with her.

This scene is the definition of the meme, If he wanted to, he would.

The creatives behind the series don’t assume that viewers are too dense to understand what isn’t being said (or depicted). Rather, they expect viewers to feel the emotions that induce anger, tears, and hesitation, even as we fight to suppress those feelings. They lay out the story arcs so engagingly that we understand the whys without needing the reasons spelled out for us.

What makes this K-drama so special isn’t the gorgeous scenery or its equally attractive cast. It’s the normal life that so many people worldwide can relate to. After all, what life is more relatable than one filled with hardship and uncertainty, even when there is love?

Warning: Major spoilers for “When Life Gives You Tangerines” below.

When she is 10 years old, Ae-sun became an orphan. Her haenyeo[1] mother died at the age of 29[2]. (Her father had previously died while out at sea.) She has the option of living at home with her stepfather (Oh Jung-se) and continuing to take care of her younger stepsiblings. Or she can move in with her paternal uncle (Jung Hae-kyun) — her father’s younger brother — and take care of his children.

At various times in her childhood, Ae-sun lives with each family, but the constant is that she is treated like an outsider by the adults. At her uncle’s house, she sleeps in a small room where the family stores their jars of doenjang and meju — pungent fermented soybeans in both paste and block form, respectively. At her uncle’s house, everyone is served meat or fish. Everyone except her. Knowing this, it’s Gwan-sik who brings fish over to supplement her diet.

At the house her mother owned, Ae-sun’s stepfather dangles the promise of sending her to a Seoul university if she sticks around and helps him with the farm and cares for her younger half siblings. He never follows through.

These adults are technically her family via blood or marriage, but they aren’t family. Those who show her unconditional love are her mother’s haenyeo friends, and Gwan-sik.

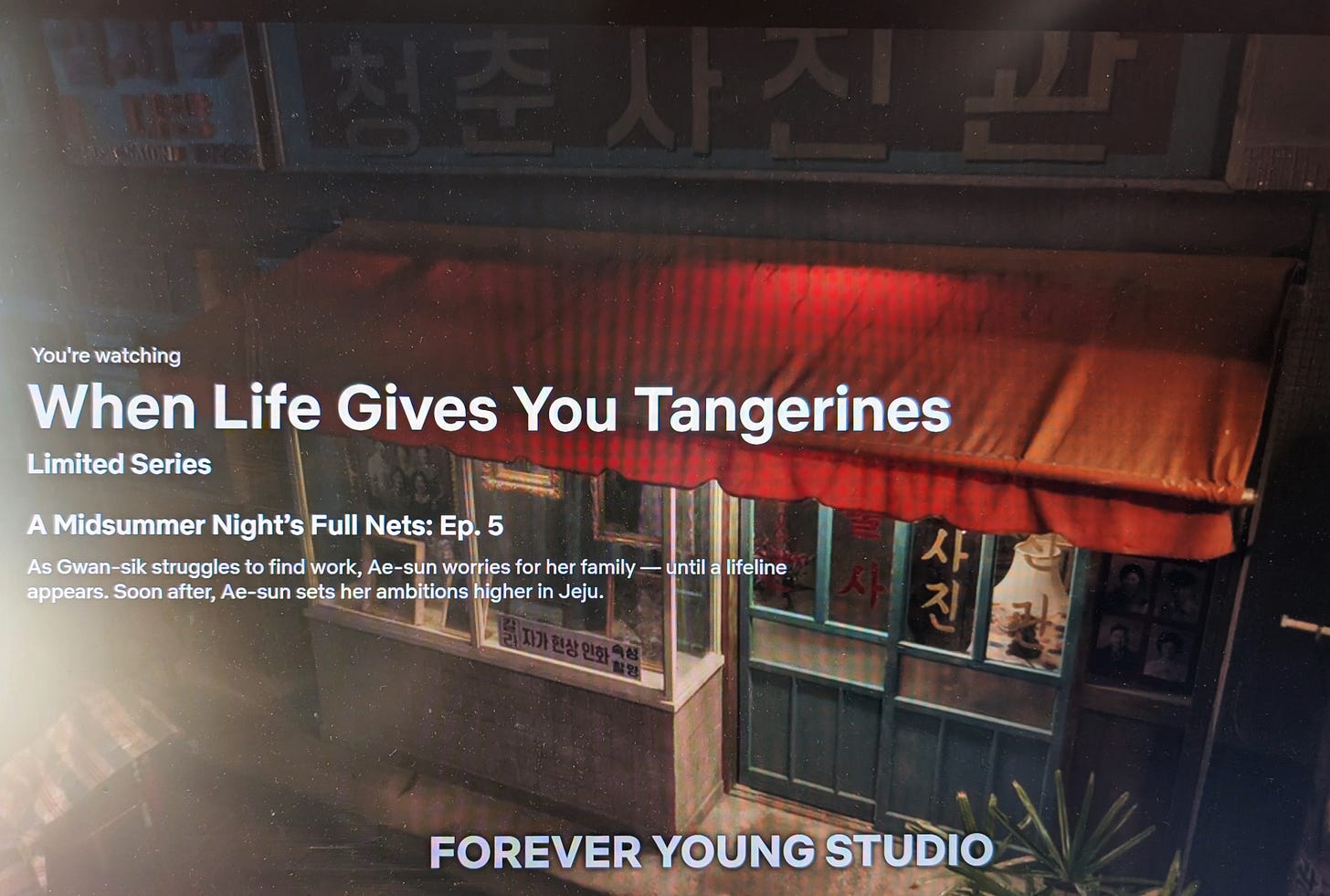

Ae-sun’s mother, Gwang-rye (Yeom Hye-ran) knows that she is dying. As is customary in South Korea, she prepares for her impending death by getting her 영정사진/yeongjeong sajin (funeral portait) taken. Apprehensive about going alone, she asks her mother-in-law Chun-ok (Na Moon-hee) to accompany her. There, Chun-ok has her 영정사진 photo taken as well.

If you look at the Hangul at the top of the photo above, it says: 청춘사진관, which translates to Youth Photo Studio or, as the subtitle says, Forever Young Studio.

Now look at the still below from the 2014 film Miss Granny.

This is a different studio, obviously. But note that it has the same name in Hangul as it does in “When Life Gives You Tangerines”: 청춘사진관.

Do I think that’s a rare name for a Korean photo studio? Not at all. Most of us want photos taken that present us in the best light as possible. And society dictates that appearing youthful is an attractive trait, no matter how old we are. So 청춘사진관 is a catchy name to drum up business.

But I do think it may have been intentional to use that as the photo studio’s name. Na Moon-hee has a prominent role in WLGYT and also portrays the titular character in Miss Granny. In the film, her new life begins after she leaves the photo studio. (This is one of my favorite movies. It’s worth watching if you enjoy films with a time travel element that will also make you bawl like a baby during pivotal moments.)

We could discuss the way women are mistreated by their mothers-in-law in traditional societies, including Korea. But what WLGYT makes clear is that kowtowing alone can’t keep peace in the family unless you disregard the wife’s feelings.

When Ae-sun married Gwan-sik, it was assumed that his mother (and his grandmother) could treat her like a servant, just as each had experienced from their own respective in-laws. And for a while, the young couple accepted it. But when the abuse became unbearable for him to witness, he didn’t try to change the mindset of his mother and grandmother. Rather, he extracted his wife from his family home and moved them into the home she had grown up in. Was this commonplace in real-life Korea? Not at all. But again, this series is a fairytale of sorts with parables meant to reflect on how the past can impact the future.

Korean women don’t change their surname upon marriage. The exception was during the period when Japan had colonized the country. Koreans were forced to take on Japanese names, speak Japanese, and abide by Japanese customs, which dictated that a woman had to take her husband’s last name upon marriage.

There are two lines of thought I have about Korean women keeping our surnames after marriage. The first is that it’s a progressive tradition that gives women ownership of our own lineage, while also honoring our own bloodline. But it could also be argued that having a different last name than our husband and children could also be a sign that women are never accepted into the families we marry into.

It’s no coincidence that not so long ago, the fathers almost always won custody of their children when a couple divorced. The thought was that the children carryon the father’s bloodline and name, not the mother’s.

I wonder if that’s why mothers-in-law feel OK about making demands of their daughters-in-law that they would never impose on their own daughters.

An example of this occurs when Ae-sun’s MiL and grandmother-in-law suggest that since it’s good luck to have a haenyeo in the family, she should encourage her young daughter, Geum-myeong, to become one. What kind of woman would actually encourage her own family member to train for such a dangerous job, especially knowing that Ae-sun’s own mother had died from complications of being a haenyeo? Who? Maybe someone who viewed Ae-sun and her daughter as disposable members of the family.

Although Ae-sun accepted most of the thoughtless treatment that her in-laws thrust upon her, she refuses to allow her daughter to be viewed as less than. She tells her mother-in-law that if being a haenyeo is such a great job for a girl, her MiL should encourage her own daughter (Gwan-sik’s baby sister) to become one. That suggestion doesn’t go over well.

A woman’s role was often dictated by the men in her family. Ae-sun’s paternal grandmother clearly loved her very much. But as a woman living in her youngest son’s home, and as the mother of a son who had already died, she didn’t have the power to stick up for Ae-sun more. But she took care of the girl in her own way.

Keeping the promise she made to Ae-sun’s mother, she gives her granddaughter all the money she had earned over the decades selling gukbap/국밥 — soup with rice cooked in it. Ae-sun gives that money to Gwan-sik to buy a small fishing boat.

By the end of the series, Ae-sun will have reconciled with her in-laws. And Geum-myeong will have turned down a sweet man (Lee Jun-young) she loved — who wasn’t strong enough to sever ties with a mother who hated Ae-sun and her family — for a man (Kim Seon-ho) whose own mother adored her like she did her own son. The daughter had grown up understanding that she had choices.

There is a story arc where Ae-sun decides to sell their beloved house — the house that she had grown up in. It’s a connection to her deceased mother. But as much as she loves that house and the memories it holds, she loves her daughter more. She decides to sell the house and move her family into a shabby little apartment so that Geum-myeung can study abroad in Japan for a year. Geum-myeung didn’t asked her to make this sacrifice.

To many viewers, this may appear to be a hyperbolic and unrealistic scenario. To me, it’s reality. My older cousin’s family did this when their daughter was accepted into Seoul National University. They sold their house and moved to Seoul to fund her education and also be nearby to support her during her university years.

When my father was laid off the summer before my second year of college, my parents made the decision to sell their house so that I could continue attending my very expensive university. My brother — who was already out of college and working — said he could pay for my tuition. Thankfully, it never came to that. But that’s what my family was willing to sacrifice for me.

Like my parents, Ae-sun wanted her daughter to have everything that she didn’t have as a child. But that kind of parental sacrifice can also place undue burden on the child. If they don’t succeed, their parents could lose everything. The pressure of knowing that your parents literally gave up their home for your education is a weight that can be tough to bear.

Throughout the series, the couple raise their daughter to be confident and strong, but to know that she always has a home to return to. Gwan-sik repeats throughout the series, “Run back to me if you have problems, OK?”

They are such good role models for Geum-myeong, but they don’t offer the same kind of latitude for their surviving son, Eun-myeong (Kang You-seok). Maybe it’s because he’s a bit of a screw-up, or perhaps because they expect more from their son. But their lack of support for him seems to be rooted in his not being smart like his sister. It isn’t until he breaks down and says that he’s no less their child than Geum-myeong that his parents seem to realize that love shouldn’t be conditional or meted out as a reward.

When your parents die, you’re an orphan. When your spouse dies, you’re a widow(er). But when your child dies, the loss is so profound (and unnatural in the order of life) that there is no word to describe the pain.

In the sixth episode, there is a scene that will haunt Ae-sun forever. After a neighbor alerts her that Geum-myeung is injured, she rushes out to rescue her daughter. She tells her young sons to stay home until she returns with their sister. The boys are only five and three years old. Scared to stay home without their parents during a typhoon, they rush outside and run off in different directions. The youngest drowns. Grieving, Ae-sun is haunted by her last encounter with her toddler. She had scolded him for grabbing a piece of candy. Angry, she brushed him aside as he begged her to hug him.

Later, a grown-up Geum-myeung busily lives her own life. So when her parents call to remind her to eat, or to ask if she needs more banchan, or wonder when she’s going to return to Jeju to visit them, she is annoyed and curt with them in the way that children can behave to parents that they know love them. But when her father gets ill and dies, and when she sees that her now elderly mother will be left alone, Geum-myeung feels the kind of universal guilt that children understand.

She watches as hospital clerks brush aside Ae-sun, treating her mother like she’s a dunce for not understanding everything they are curtly explaining. Geum-myeung lashes out at them, not just because of their insulting behavior, but also because she can’t bear to watch her strong, feisty mother accepting their rudeness.

I often see platitudes and memes on social media that essentially say, “Your parents are only getting older. Spend every single moment you have with them now.” And while that’s an admirable sentiment, it can also create an unrealistic burden. The life that our parents gave us isn’t meant to be monopolized by them or make us beholden to them, no matter how wonderful they are. They gave us life, knowing that our independence would mean they will have less interactions with us. To expect children to be tethered forever to their parents is a punishment of its own. (And I say this as the daughter of an elderly mother; and as the mother of a teenager.)

I read this comment on Reddit that gets across what it means to feel the guilt and turmoil of seeing your parents age and prepare for their death:

Condolences: Kang Myung-joo played the woman we all loved to hate in this series. As the overbearing mother of Geum-myeong’s first boyfriend, Yeong-bum (Lee Jun-young), she was icy cold and very much a beeeeyeeeeeooooottttch who cared more about status than what her son wanted. Kang died of cancer on February 27, 2025, just one day before her 54th birthday, and a week before WLGYT premiered to worldwide acclaim. May she rest in peace.

Airdates: Sixteen hour-long episodes aired on Netflix from March 7 to March 28, 2025. Four episodes were dropped each week on the streaming app. (I watched the series on Netflix.)

Footnotes:

[1] Haenyeo translates into sea women and refers to the female divers of Jeju-do who harvest seafood by freediving 32-feet in the sea, without utilizing oxygen tanks. The strenuous haenyeo life was also depicted in the K-drama “Welcome to Samdal-ri.”

[2] Ae-sun’s beloved mother is portrayed by Yeom Hye-ran (“Uncanny Counter,” “Mask Girl”), who is a wonderfully skilled and nuanced actress. But I question her casting. At 48, it is a stretch for anyone to be believable as a character who is at the tail end of their 20s. And she shouldn’t be expected to. I suppose the argument could be made that her difficult upbringing and life had aged her immensely. But I think a better option would’ve been if the character had been an older woman who became a mother later in life.

K-DRAMA INDEX

These are some of my reviews and essays about K-Dramas (and also Korean films and other Korean-centric projects). You may also read more about my take on Korean pop culture in outlets such as Rolling Stone, Mashable, Victoria & Al…

© 2025 JAE-HA KIM | All Rights Reserved